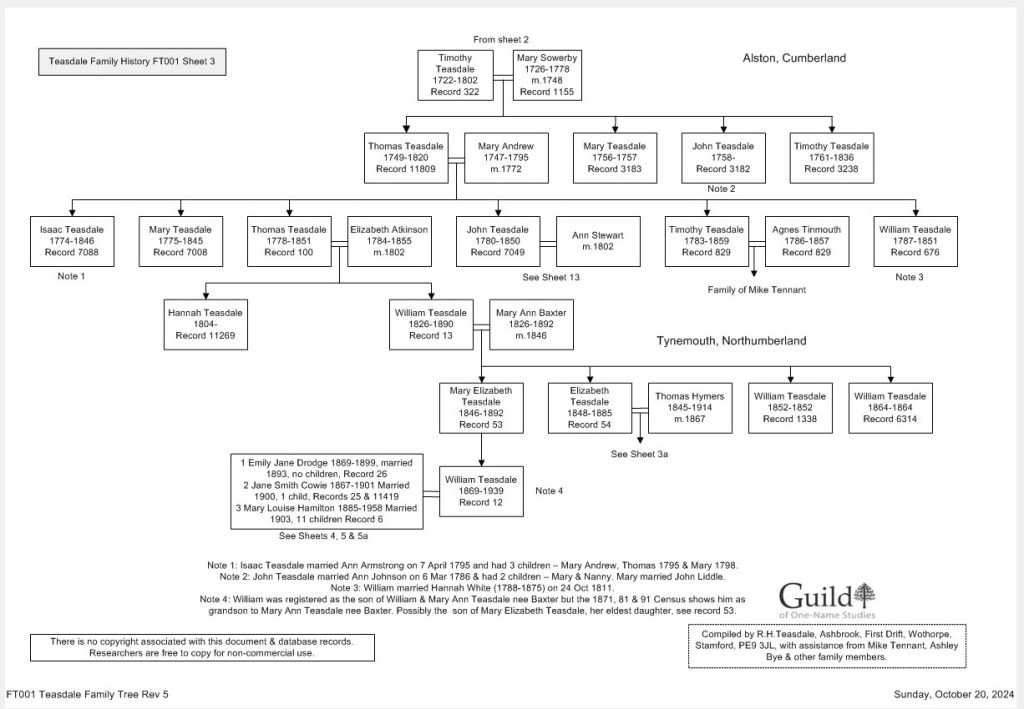

Between 1837 and 1965 about 4% to 7% of children were illegitimate. In the early 18th century, the rate was probably lower at around 2%. It was common in earlier centuries for a couple to marry only after the girl became pregnant or even after she produced a child. Children were a guarantee of support for the parents in later life who could end up destitute on parish handouts. The dreaded workhouse became available in the nineteenth century. The identity of the parents in these cases was recorded and the child was recorded as legitimate. If your ancestor was born to an unmarried woman the parish register may not have identified the father. If a father is not named in a parish register, other records may be available. Parish overseers wanted to know who he was so they could make him liable for maintenance. Neighbours & villagers in the 16th to 19th centuries usually knew who the father was and this could recorded in parish or Justice’s records. A statute in 1610 provided that mothers of bastards could be sent to a house of correction for up to a year & were often whipped. Many of us today, researching our family trees, are likely to find illegitimacies and my own family is no exception. From 1869 all our Teasdale family tree is derived from Mary Elizabeth Teasdale 1846-1892. She had an illegitimate child, William born 1869 & he was registered as the child of Mary’s parents William & Mary Ann Teasdale, nee Baxter. I thought all was normal until one day I examined the census returns for 1871, 81 & 91, only to find William born 1869 was described as the grandson of William & Mary. You need to bear in mind that the civil registrar near the town hall was usually anonymous but the census enumerators visiting your home were recruited from the local population. I have correspondents whose families were broken up & the child adopted, right up to the 1950s. We think nothing of illegitimacy now, it is relegated to history where it belongs. We must be aware of pre-judging our ancestors with our modern outlook.

I’ve read your website, and thankyou! I’m a Teasdale by birth, unfortunately my father died tragically before I was born and like wise his brother in separate incident, so there was never anyone to ask (my mother just couldn’t). I’ve often wondered where we hailed from and how old the name was thought to be. Keep up your labour of love!

LikeLike